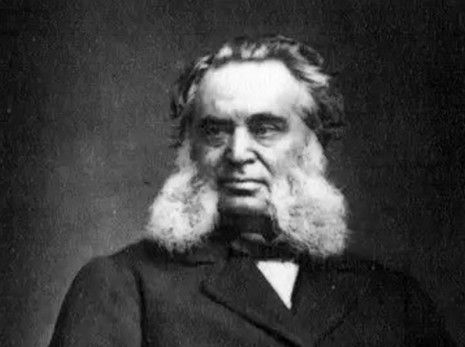

Thomas Youdan - Theatre Proprietor

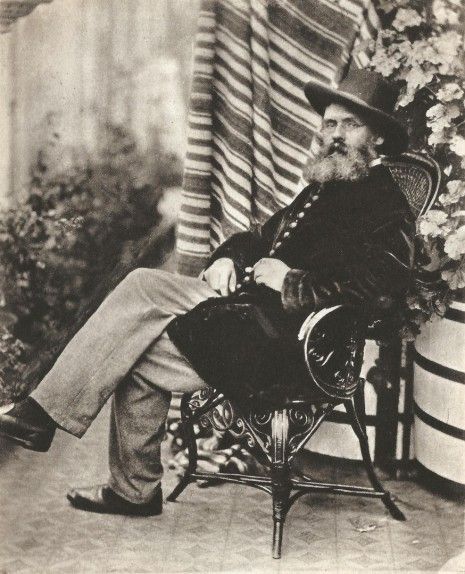

Thomas Youdan (centre in tall hat) and theatre company, 1865

Thomas Youdan lived in Totley for less than two of his sixty years but it is for what he did whilst he was here that he is best remembered. The Youdan Cup was the world's first knockout football competition held in 1867 between twelve teams from the Sheffield area with the final played at Bramall Lane cricket ground. The silver trophy was created by Ebenezer Hall's firm, Martin, Hall & Co. When it appeared on Antiques Roadshow in 2008 it was valued to be worth at least £100,000 by silverware expert Alastair Dickenson. We thought it was high time that we found out more about the man whose name it bears.

The Early Years

Thomas Youdan was born in Streetthorpe near Doncaster in 1816, the ninth of ten children of Samuel Youdan, an agricultural labourer, and his wife Hannah (Anne) Hall, who were married at Kirk Bramwith, Yorkshire on 30 June 1800. All of the Youdan children were baptised at St. Oswald Parish Church, Kirk Sandal: George (24 January 1802), Charles (24 April 1803), Hannah (22 November 1804), Sarah (12 July 1806), Samuel (5 December 1808), Anne (1 April 1810), Robert (19 January 1812), Jane (2 February 1814), Thomas (19 May 1816), and John (28 June 1818). Charles was the only one who died in infancy. He was buried at St. Oswald's on 10 June 1805.

As a young man, Thomas worked with his father as an agricultural labourer but in 1834, at the age of 18, he decided to follow a number of his brothers who had moved to Sheffield seeking work. At first he was employed as a labourer with the firm of James Dixon & Sons of Cornish Place, Neepsend. Trade was very brisk and Thomas took the opportunity of learning the art of silver plating. He was a clever workman and subsequently found employment as a silver stamper for a number of the large firms in Sheffield.

His career changed after his marriage to Mrs. Mary Bodger, a widow, on 26 November 1843 at Sheffield Parish Church. Mary was born in Rotherham on 31 August 1816, the daughter of Mary and Thomas Naylor, a miner. She married Emmanuel Bodger at Sheffield Parish Church on 24 January 1838. Their daughter, Mary Jane, was born on 19 April 1840 but she sadly died later the same year and was buried at St. John, Park on 27 December. Emmanuel was a brewer and publican who ran the Brewer's Arms at 28 Broad Street, Park until his death at the age of about 27, on 27 August 1843. Thomas Youdan took over the beerhouse following his marriage to Mary and by July the following year Thomas had a second house in Hartshead.

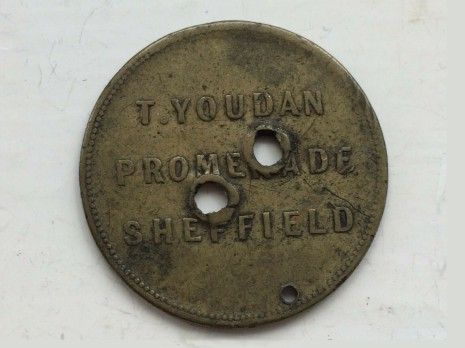

Youdan's Royal Casino entrance token

The Surrey Music Hall

Thomas was an ambitious man who had plans to bring high quality entertainment and attractions to his clientele. By 1848 he had moved to a larger property at 66 West Bar which he called Spink's Nest, located where the Law Courts now stand. It had been a well-known pawnbroker's shop run by John Spink until his death on 30 July 1846 at the age of 61. The shop stood on a large corner site that was all owned by Mr. Spink and which totalled about 1,200 square yards. There were three further shops facing on to West Bar, all with dwelling houses behind, and thirteen dwelling houses facing on to Workhouse Lane. To the rear there were stables and a large communal space, known as Spink's Yard. Thomas soon expanded the beerhouse into adjacent buildings and made a concert room and stage which was big enough to put on impressive performances. Fully refurbished throughout, Youdon's Royal Casino opened to the public on 17 March 1849 with musical entertainment every evening and on Monday and Tuesday afternoons.

At the annual Brewster Session held at the Town Hall on 31 August 1849, Thomas's application for a wine and spirits licence was refused by the Bench. Such licences, it was said, were granted to houses to supply refreshments to travellers. The Royal Casino was more like a theatre and although Manchester, Liverpool and other large towns had granted full licences to theatres, Sheffield had not and it would set a precedent.

A further application was made the following year when it was pointed out that Thomas had spent £1,700 to adapt the building to its current purpose. Its concert room could now hold 1,500 people and no fewer than 10,000 people had visited the building during the previous Christmas week. The Casino was closed on Sundays and would remain so and would close at a time in the evening as specified by the magistrates if a licence were to be granted. A policeman was in permanent attendance paid for by Thomas. Although the magistrates acknowledged that it had been proven that the place was conducted in a respectable manner, the licence was again refused for precisely the same reason as before. Application and refusal were to become recurring annual events. Nevertheless the Royal Casino continued to be highly profitable based presumably upon huge beer sales alone as, initially at least, entertainment was offered each night entirely free of admission charges.

It was not only alcohol that was subject to licensing laws. The Regulation of Theatres Act of 1843 required licences for all manner of performances. Thomas often found linguistical contrivances for describing operas and dramas to avoid falling foul of the law. In July 1850, however, he rendered himself liable for a fine of £20 for each of the eighteen nights on which a Mrs. Montgomery gave operatic performances. His defence was that she had been engaged to perform in the ballet Mad as a March Hare, although Mrs. Montgomery had never danced professionally in her life. In September 1850 Thomas changed the name of his establishment from Royal Casino to the Surrey Music Hall. No doubt the name was chosen to draw comparison with Sheffield's most respectable concert hall which was the Music Hall in Surrey Street. Most people continued to call it The Casino.

In the census on 30 March 1851, Thomas and Mary were recorded at 66 West Bar. Curiously, Thomas was described as a silversmith and beerhouse keeper. He never lost his affection for the Sheffield silverware and cutlery trades. With them were a domestic servant and two of Thomas's nieces. Emily Youdan was aged 17 and a barmaid and her sister Harriet was aged 7, the youngest of nine children of Thomas's eldest brother George Youdan, who had married Mary Hudson at Holy Trinity, Hull on 28 March 1826. George and Mary were running a beerhouse in York with three of their sons.

When James Scott moved from Manchester to take a lease on a massive old circus building in Blonk Street and convert it into the Adelphi Theatre, Thomas responded by rebuilding the Surrey Music Hall with an increased capacity of 3,000. It reopened in November 1851 and the following month, Charles Dillon, the lessee of the Theatre Royal charged Thomas with having allowed his premises to be used for the public performance of an unlicensed stage play called Love in Humble Life. Thomas argued on a technicality of law that a performance consisting of dialogue, songs, posturing, music and dancing was not a play which under the law was defined as "every part of tragedy, comedy, farce, opera, burletta, interlude, melodrama, pantomime or any part thereof". The case was dismissed but further cases continued to be brought against him the following year, most notably by James Scott. The Bench recognised that business rivalry was at the heart of the matter and fined Thomas just £5.

On 19 May 1853 Thomas's wife Mary died in Rawmarsh whilst staying at the home of her brother Samuel Naylor, a coal miner. She was aged 36. She was buried at St. Lawrence, Rawmarsh four days later. There were no children from her marriage to Thomas who never remarried. After further nominal fines for staging unlicensed entertainment, Thomas was again taken to court by James Scott in January 1854. It was proven that the Surrey Music Hall had put on event called Chinese Carnival which was an unlicensed pantomime. It played to full audiences whilst the Adelphi had lost money on a properly licensed event that was badly attended. Thomas was fined 42s. and warned by the magistrate against staging further unlicensed seasonal events at Easter and Whitsuntide.

Thomas finally applied for and was granted a three month theatrical licence in 1854 but he allowed it to expire when the court made it crystal clear that his beerhouse licence would not be renewed to run concurrently. Moreover, he would not be permitted to flip-flop between holding the two licences at different times of the year as and when it suited him. The beer licence was the more valuable and, despite repeated assurances to the contrary, the fines for unlicensed performances continued.

The Crimean War Memorial, Moorhead, Sheffield

The Crimean War

0n 3 January 1856 Thomas announced that he had asked the confectioner George Bassett to bake an enormous twelfth (i.e. twelfth-night) cake to celebrate the end of the Crimean War with Russia. The cake was to be sold at 1s. 6d. per one pound portion to visitors of the Surrey Music Hall on 31 January and succeeding nights. Tickets were sold in advance entitling admission and a portion of cake. Newspaper advertisements said that the cake would contain 154 randomly placed and individually numbered medallions which would entitle the holder to share in "gift money" of £200 divided into prizes with values between 10s. and £10. However, after more than 7,000 tickets had already been sold, Thomas was forced to announce that no prizes would be distributed. He had been warned by John Greenwood, Assistant Solicitor to H.M. Treasury, that if he went ahead with the scheme as advertised he would face prosecution for an illegal lottery. Thomas offered to return the money to anyone who applied for a refund but, apparently, very few did as the price of the cake was very attractive.

When assembled, the cake was between 8 and 10 feet in diameter and 9 feet high and weighed around 4 tons 8 cwt (9,860 lbs). The recipe comprised 1,830 lbs. of sugar; 1,360 lbs of butter; 3,410 lbs. of fruit; 2,050 lbs. of flour; 1,020 lbs. of candied peel and 10,500 eggs. It was baked in sections and united into one mass with 424 lbs. of icing. It was conveyed to the music hall from Mr. Bassett's bakery in Broad Street, Park by three drays, drawn by two horses each. It was originally intended to lay down rails to convey the cake to the front of the stage but this was not feasible and it was positioned at one end surrounded by drapery and festooned by flags of the nations. So many people had asked to see the cake that it was exhibited for three days before it was eventually cut into portions and distributed to ticket holders.

Whilst most people were happy that they got a bargain there were complaints from a sizeable minority that their portion of cake was not properly cooked. In theory this should not have happened because the cake was built up from smaller individual cakes. Mr. Bassett eventually confessed that "some small portions were rather soft" (an understatement) and suggested that by adding a little flour and suet, and mixing with milk, the cake could be converted into "as good and as cheap a plum pudding as could be made." Thomas was not blamed, particularly when it was demonstrated that he did not make a profit from the sale having paid between 11d. and 1s. per pound to Mr. Bassett, and had the costs of printing, advertising and distribution to pay as well.

The Treaty of Paris which concluded the war was signed on 30 March 1856. To celebrate the end of hostilities, Thomas put on a Grand Gala at Newhall Gardens, Attercliffe on 23 and 24 July, featuring the band of the Surrey Music Hall and a variety of singers, dancers, gymnasts etc. A firework display representing the Siege of Sebastopol was performed in front of a giant mural of the scene covering 90,000 square feet of canvas. Admission was 6d. It was so successful that two further events were held at the same location featuring a number of military bands. For the second of those events, Thomas had purchased from George Wostenholm of the Washington Works, 222 top quality, six-bladed spring knives as gifts for the surviving officers and men of the 4th Dragoon Guards. Each knife was inscribed with the soldier's name and rank. 140 were presented at Newhall Gardens on 8 September and the remainder were sent to Leeds and Bradford to be presented there.

To conclude the peace celebrations, Thomas made arrangements for an extraordinary outdoor tea party. Applications for free tickets were invited from 2,000 old women aged 60 and upwards. The Duke of Norfolk gave his permission for the event to take place on a site adjacent to the Cattle Market by the side of the River Don, close to Sheffield Victoria Station. Tables were laid and decorated with flowers. Mr. Thompson of Church Gates was contracted to supply the catering. As with the monster cake, the quantities were enormous and included 800 lbs. of spice cake; 400 lbs. of bread; 160 lbs. of butter; 90 lbs. of tea; 400 lbs. of lump sugar and 60 gallons of cream and milk. Two large kettles were borrowed from the Temperance Society. At a quarter to five on 18 June 1857 the crockery had been placed on the tables and most of the guests had arrived, dressed in their finest clothes, when the heavens opened. Thomas was hard pressed to convey the old ladies to the shelter of the nearby railway arches and thence home. The spice cake was offered for sale at a cheap rate and a fresh batch ordered for a week hence when, thankfully, the event took place in perfect weather. One of the top tables was reserved for the nineteen very oldest ladies whose combined age was 1,668 years. The tea party was watched by up to thirty thousand spectators. It was followed by a ball which was attended by an estimated 12,000 people.

At the beginning of 1856 a group of men from Sheffield's clubs and lodges - Thomas sponsored Oddfellows and Foresters lodges - formed a committee with the purpose of presenting Thomas with a testimonial for the many good deeds he had done for them and for the ordinary working people of Sheffield. When approached in September, Thomas declined their offer saying he had done nothing to merit such an honour but instead proposed that the money they had raised should form the nucleus of a fund to build a monument to the memory of those soldiers and sailors who had lost their lives in the Crimea. Thomas placed newspaper advertisements seeking relatives and friends to furnish him with the names to be inscribed on tablets and engaged the sculptor Edwin Smith to produce designs.

However, his idea quickly caught the imagination of the Sheffield public and it was thought that the memorial should be the work of the town not of a private individual. His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge was invited to lay the foundation stone and Florence Nightingale was invited to attend. She declined but she and her family made generous contributions to the fund. The Duke duly laid the foundation stone at Moorhead on 21 October 1857. In the evening after the formalities were concluded, Thomas entertained about fifty Crimean veterans to a sumptuous dinner at The Grapes Inn, Trippet Lane.

When he was later asked to explain his interest in the Crimean War, Thomas said that he had six nephews in the army and navy, four of whom had served in the Crimea and were currently in India and who might not return home. He felt the need to recognise their service to their country and the devotion to duty of similar men, particularly those who had lost their lives.

Mr. Cantelo's Patent Hydro-Incubator

The Museum

It was also in 1856 that Thomas decided to convert the floor below the theatre into a museum and art gallery and began to fill it with all manner of curiosities from nature, art, invention and manufacturing.

Whilst some of the natural history specimens were stuffed, others were very much alive. On 16 April Thomas attended a sale at Wingerworth Hall, Derbyshire to bid on the wildlife collection of the late Sir Henry Hunloke. Thomas's purchases were reported in the Derbyshire Courier three days later:

Lot 91, a pair of Wolves from Sweden, £19 19s.

Lot 97, a brown Bear from Sweden, £26 5s.

Lot 98, a very handsome Russian Bear, £11 11s.

Lot 102, a pair of Esquimaux Dogs, £7.

Lot 110, a nasicus Cockatoo and cage, £4.

Lot 112, pair of Alexandrine Parroquets, £5 5.

Lot 113, a Leadbeater Cockatoo, cage and stand, £7 5s.

Lot 114, a cream white crested Cockatoo and cage, £1 16s.

Lot 118, a penantian and small Parroquets and cage, £7.

Lot 119, Chinese Lory and cage, £2 10s.

Lot 122, blue and yellow Macaw and stand, £1 10s.

Lot 126, Cantelo's patent incubator, or egg hatching machine, £5 10s.

Newspaper reports suggest that almost two thousand people attended the sale. Competition was spirited, except for Lots 91, 97 and 98, the wolves and bears, which realised only a fraction of their original cost. The Swedish bear was described as the biggest in the country. The Surrey Music Hall was closed for several weeks whilst it was adapted to create a menagerie.

In November 1856 Thomas bought a further collection of exhibits from the estate of the late William Younge of Endcliffe including geological specimens, antiques and other artifacts from India, Africa, the Sandwich Islands, Egypt and Pompei. A golden eagle, shot during the war with Russia, was presented to the museum by a Crimean veteran. More than £1,400 had been spent on the museum alone, at a time when there was no public museum or art gallery in the town. Even people who had no interest in the music hall brought their children to see the attractions.

Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 2 April 1857

Thomas employed a man called Tom Smithers to look after the animals. He was faithful and hard-working but liked a drink. He had been given strict orders not to leave the premises after the music hall was closed but one evening Thomas heard him on the staircase and supposed him to be fetching whisky. Intending to give him a fright in order to teach him a lesson, Thomas went down to the menagerie and locked the door behind him. Presently he sensed something was moving around in the room and then saw the two bears closing in on him. Although very frightened he had great presence of mind to climb in their cage and managed to partially lock it. The bears growled and shook the cage for what seemed to Thomas like half an hour until Tom returned to find the door locked and his governor shouting. Tom quickly made a plan, forced open the door and entered with a flaming torch in one hand and a bucket of bear food in the other. He managed to get the bears into an empty cage and then freed a terrified Thomas. Soon after, the bears were sold.

To raise the importance of the museum in the community even further, Thomas wanted to exhibit the finest of local skills and craftsmanship. There was no more important trade in Sheffield than cutlery and Thomas proposed holding a contest amongst spring blade cutlers with fourteen prizes awarded to the best in class totalling £50. To encourage entry and to make sure that no contestant was out of pocket, £15 was left in the hands of the adjudicators to award as they saw fit. Ownership of the knives would rest with Thomas who would place the knives on exhibition in the museum but he would not own the design. Entries were to be submitted by 1 January 1857 for evaluation as soon afterwards as feasible. In the event it was not until mid February that the decisions of the judges were announced. First prize went to John Sanderson of Jericho Street, who worked for Joseph Rodgers & Sons, for "excellence of design, utility and workmanship".

The Guardians of the Poor had established a model farm at Hollow Meadows, Bradfield to give unemployed men of the Sheffield Poor Law Union work that would be more useful, productive and healthy than they would otherwise have had in the workhouse. On 14 December 1857 Thomas placed the Surrey Music Hall and its entire company at the disposal of the farm committee to raise funds to provide a Christmas dinner for the unemployed and their families. The house was well filled and the benefit raised the sum of forty pounds which was spent at Rotherham market on two heifers. The animals were slaughtered and the meat weighing 120 st. (1,680 lbs) was shared amongst 175 men, 148 women and 470 children according to family size. A family of two adults and six children received about 12 lbs of beef. It was to be the first of what became annual benefits for the unemployed.

In Court Again... and Again... and Again

Thomas had been fined for breaches of various sections of the Theatre Act in May and August 1857 but worse was to come when on 18 January 1858 he was tried and found guilty of breaking the Lotteries Act. Thomas had been in the habit of attracting enormous audiences by announcing monster raffles but the facts of this case were not straightforward. On 13 January 1858 he announced there was to be a sale of cakes. After paying the entrance fee to the music hall, a ticket was issued bearing a unique number. If that number was later called out from the stage, the bearer of that ticket could bid for a cake against a reserve price. When all of the cakes had been distributed, successful bidders were invited backstage where it was explained that the cake was theirs of right or they could accept a cash alternative if they so preferred. One witness claimed to have bid 8s. against a reserve price of 7s. and later been offered a 5s. cash sum in lieu. Having heard all the evidence, the magistrates decided that since money had been received for all the tickets but cakes given to only certain ticket holders, it was in fact a lottery. Thomas received the minimum sentence under the law: a fine and seven days imprisonment in one of Her Majesty's houses of correction. He was allowed to remain free pending an appeal.

The appeal to the Court of the Queen's Bench was heard on 22 April. It confirmed the decision of the Sheffield magistrates and imposed costs. Five days later a meeting was convened in Sheffield Town Hall to consider a petition to the Secretary of State. By now Thomas Youdan was quite possibly the most popular man in Sheffield thanks to the enjoyment he brought into the lives of so many ordinary people and through his many charitable acts especially to the poor and infirm. The meeting was packed and over a thousand signatures were gathered in under two hours. Speeches of support were given from prominent men who had no personal connection with Thomas or with his music hall. In the middle of the evening a telegram was received from Thomas's lawyer in London and read out to the audience announcing that the Queen would be advised to grant a pardon conditional upon Thomas giving a written undertaking not to re-offend. His arrival at the Town Hall shortly afterwards was greeted with cheers and applause.

Thomas was back in court the following month but this time as a witness to an incident at the Surrey Music Hall on 13 September 1858 when five people died in a panic to escape the theatre after a flash and explosion had occurred in the gallery, followed by shouts of "Fire!". The four men and one women were all local people under the age of 24. Verdicts of accidental death were brought in on all five: William Dale died as a result of jumping through a window whilst Ellen Staley, Frederick Morton, Philip Child and Alfred Sales were suffocated in the stampede down the stairs. Many more were injured. Thomas had been in his room when the incident occurred and was told a shot had been fired. He was quickly on stage to encourage the audience to remain calm and seated. No doubt his quick intervention prevented a far worse catastrophe.

There was no fire, except later to a woman's cloak, which was thrown onto the stage and which Thomas trampled out. The cause of the flash, whether from pistol fire, gas explosion or some other source could not be established despite the most careful collection of evidence by the police and a thorough examination by the coroner. The music hall had reopened only three days earlier following seven weeks of alterations and refurbishment when new gas-lit chandeliers were fitted.

On 25 October 1858 a quite different court case was brought against Thomas when he was summoned to show why he should not pay for the support of an illegitimate child of which the mother, Miss Selina Bollington of Bramber Street, Brightside alleged he was the father. Thomas denied the allegation and the law required that the evidence of the mother must be corroborated on some material point. Selina said that she had been employed by Thomas as a barmaid since 9 November 1857 and lived at the Surrey Music Hall. She claimed that Thomas had slept with her on two nights in his niece's room whilst she was away at school. There were no eye witnesses or even proof that Harriet was away and the court relied heavily on the word of Selina's mother, Sarah, a widow of thirteen years, in adjudicating against Thomas and ordering him to pay 2s. 6d. per week maintenance until the child's thirteenth birthday plus legal and medical costs.

Thomas appealed against the adjudication and, even before the case was heard, he had published evidence to show that both Selina and her mother had given false testimony. Sarah Bollington had remarried to Cawthorne Wright, a cutler, on 11 April 1854 at Sheffield Parish Church and, although separated, they were still married. Thomas lost his appeal and never acknowledged the child to be his own.

Selina Bollington was born on 23 July 1842 at Shirebrook, Derbyshire, the youngest of five children of Job Bollington, a joiner, and Sarah Brushfield who married at Mansfield Woodhouse on 24 August 1829. Her father had died in 1846 when she was aged four. She was aged 15 when she became pregnant. Her son, Thomas Youdan Bollington, was born on 21 September 1858 and baptised on 4 November 1860 at Sheffield Parish Church. After his mother's marriage, he used the name Thomas Rutherforth Bollington, taking the surname of Selina's husband, George Rutherforth. When he married Mary Elizabeth Boothroyd on 11 December 1877 young Thomas gave his father's name as the fictitious George Bollington.

Councillor Youdan

Thomas claimed that the bastardy case was politically as well and financially motivated. It was brought before the magistrates court at a time when he was being talked about as a possible candidate for St. Philip's (Shalesmoor) Ward in the upcoming elections for Sheffield Municipal Council. After the verdict, his opponents and even some of his supporters suggested that he withdraw his candidacy. The appeal would not be heard until after the election but Thomas begged the burgesses (voters) to suspend their judgment on him until the appeal had been heard.

On the day of the election, Thomas made himself conspicuous by driving about about in an open omnibus, bringing his supporters to the poll. Dressed in a shiny white top hat and light suit, his behaviour was considered more in tune with a man of the turf conveying racegoers to Doncaster than that a future town councillor. Nevertheless when the election results were declared on 2 November 1858, it was Thomas that topped the poll and he was duly elected for a term of three years. In thanking his supporters, he undertook to resign should his appeal fail. When the verdict was known, and whilst still protesting his innocence, he immediately tendered his resignation to Charles Bagshaw, the chairman of the St. Philip's Ward committee but it was declined until such time as the burgesses called upon him to go.

Thomas was also elected to the Board of Guardians for Sheffield. Although not a well educated man, Thomas was able to make an effective contribution to both public roles, championing the causes of the common people, particularly the unemployed, poor, elderly, sick, and children of the workhouse school.

In June 1859 Thomas announced his intention to retire from the day-to-day management of the Surrey Music Hall but would still remain as the proprietor. The Surrey Music Hall was being rebuilt for the third time, this time to a grand design by the respected Sheffield architects Messrs. Flockton and Son. When it reopened in July, the manager was Michael Donnelly (1827-1882), an Irish tenor vocalist. In December 1859 the reason for Thomas's change of circumstances became evident when it was revealed that he had taken a seven-year lease on the Adelphi Theatre and was intending to completely refurbish it. A theatre licence was granted the following year on the basis that the Adelphi would sell neither beer nor spirits. The Adelphi was to be managed by John Coleman (1832-1904), a Derby-born tragedy actor who later became well-known as the manager of the Leeds Theatre Royal.

Thomas moved residence to Lane Head House, Grenoside, taking a lease on a large four bedroom property with servants' cottage, coach-house, stables and six acres of gardens and pasture. He soon settled into his new environment, entertaining eighty old women of the area to afternoon tea and patronising the Grenoside Cricket Club and local horticultural events. When the census was taken on 7 April 1861, at home with Thomas at Grenoside were his niece Harriet Youdan, a cook, housemaid and groom.

In October 1861 Thomas was one of two councillors for the St. Philip's Ward due to retire. He had failed to attend a single council meeting during the year and it was not known whether he intended to stand for re-election. Charles Bagshaw and other committee members who had supported his nomination in 1858 switched allegiances to an opponent. Thomas certainly divided opinions and he was an easy target for criticism and abuse. It was said that his word could not be trusted as had been proven several times in court and that his philanthropy was motivated by a desire to gain maximum publicity in order to boost his personal popularity and increase profits from his business. It made little difference to the electorate for whom, it was said, deeds were more important than words. In the election on 1 November, Thomas was again the clear winner. It was then alleged that he had received ineligible votes and a full recount was ordered which threw out about the same, small percentage of the votes for all four candidates and confirmed Thomas's re-election for three further years.

Cllr. George Bassett (1818-1886), confectioner and founding trustee of Totley Methodist Chapel

Thomas showed greater commitment to attending the weekly meetings of the Board of Guardians but his popularity was no more universal. He concerned himself with the business contracts that were awarded for the supply of food and clothing to the workhouse inmates. George Bassett was another guardian and Thomas frequently complained about that quality of the bread, on one occasion throwing onto the committee table inedible bread that had been sent to him by the governor. He found no fault with the cloth supplied to the workhouse but alleged that the contract had been awarded unfairly at a far higher price than could be obtained had there been open competition. At the same time Thomas demonstrated his commitment to assisting the needy by donating £25 to the relief of distress (poverty). As winter approached he supported the creation of soup kitchens and made further donations of money, two tons of swedes and several dozen tons of coal. His niece Harriet also gave 25 tons of coal to the Park District poor relief fund.

Thomas had applied for a six months theatrical licence for the Adelphi Theatre on 30 August 1861 which had been granted. On 25 February following, he approached the court again saying that he had not used the licence as he had been persuaded that there was a greater need in the town for a public hall and was busy adapting the Adelphi for that purpose. Instead he wished to transfer its licence to the Surrey Music Hall which was a much more suited to being a theatre. He was literally laughed out of court.

In March 1862 Thomas was again nominated for election to the Guardians of the Sheffield Union. The election was equally as rancorous as that for the Council and Thomas was singled out for abuse from those claiming to represent heavily taxed ratepayers. The election on 11 April was to return eight from 22 candidates and Thomas attracted the second highest number of votes; George Bassett failed to be re-elected. The first meeting of the new board took place the following week and Thomas was appointed to the House Committee and North District Relief Committee.

Thomas's tenancy on the house at Grenoside expired on 2 May 1862 and he appears to have decided to return to West Bar to live in the ward that he represented. Before that, a huge sale of furniture, curtain, carpets, china, glassware, clocks, linen etc., plus garden tools and several horses and carriages took place at Lane Head House on 3 April. Thomas took a lease on a property at Parkwood View, Wentworth Terrace in Upperthorpe, within walking distance of West Bar.

On 21 November 1862, Thomas re-applied for a theatrical licence for the Adelphi Theatre stating that he had twice held a licence before but had not made use of it. He had contemplated converting the theatre into a public hall but had not commenced work on it and instead signed contracts to bring the theatre up to the required standard to be used for its proper purpose. The application was opposed by Charles Pitt, the lessee of the Theatre Royal on purely commercial grounds, that the town could not support two licensed theatres. After deliberation, the magistrates decided to refuse the application as it would be against the public interest. After that Thomas used the Adelphi as a timber store and as workshops for the construction of scenery for the music hall.

Tom Taylor, photographed by Lewis Carroll in 1863

After a further failed attempt at obtaining a theatrical licence for the Surrey Music Hall on 4 September 1863, Thomas returned to court twelve days later with a fresh application. It had been suggested to him by his friends that there were three things that were counting against him. Firstly, he held a licence for the consumption of beer on the premises. Secondly, if he were to obtain a theatrical licence, he could apply to the Excise, and be almost certain to be granted, a licence to sell spirits during the hours of the performance. Thirdly, the music hall had a saloon where dancing was allowed that might attract the wrong sort of clientele. On the basis that Thomas handed over his beer licence, closed his dance saloon and would not apply for a spirits licence, the Bench granted him a theatrical licence to run for six months. Although not required by law, Thomas also agreed to do what he could to enforce a ban on smoking. The court's decision was greeted with applause. The Surrey Theatre opened on 28 September 1863 with a performance of Tom Taylor's drama Ticket-of-Leave Man before a packed audience of more than three thousand. The Christmas pantomime Sinbad the Sailor especially written by Charles Horsman was an even bigger success.

The theatrical licence came up for renewal on 11 March 1864. Thomas asked for it to run for twelve months but it was granted for only six, there being no objections. On the same day, the Dale Dyke Dam broke as its reservoir was being filled for the first time and, in the resulting flood, at least 240 people lost their lives and many more their homes, livestock and livelihood. A relief fund was set up to which Thomas contributed the sum of £100.

Thomas was re-elected to the Sheffield Board of Guardians the following month, the third of the six successful candidates. After further alterations during the summer interval to the Surrey Theatre, including a larger stage and a coffee room, its licence came up for renewal 10 September. Thomas again asked for a period of twelve months and was again granted only six.

The Municipal Elections were due again on 1 November 1864. In order to avoid the unseemly events of three years earlier, the two committees had joined together to form the St. Philip's United Burgesses Association whose aim was to seek the re-election of Thomas Youdan and Richard Searle. Their nominations were expected to go unopposed but at the last moment, Joseph Nadin, a medical botanist who had been narrowly defeated in 1891, was also nominated. Scurrilous placards were published coupling his name with that of Richard Searle who thus had the support of both parties. Perhaps through overconfidence, Thomas had done little campaigning and, to great surprise when the votes were counted, he was left trailing a distant third. Under a half of those on the electoral register cast their vote. On 17 March 1865 Thomas also lost his place on the Sheffield Board of Guardians, the Burgesses Association taking the view that his poor attendance at the weekly meeting did not warrant his nomination.

Surrey Theatre Fire, West Bar, Sheffield, 1865

Surrey Theatre Fire

A week later, on 24 March 1865, the Surrey Theatre was totally destroyed by fire. Police constable Smelt, who was on the West Bar beat, was one of the first men to discover it and raise the alarm at 2.25 a.m. He had passed the building only five minutes before and had noticed nothing but when he returned he heard a cracking sound and saw flames bursting from the roof. Fire services were soon on the scene but by about 4 a.m. the building was completely burned out. So much of the theatre was made of wood: the stage, the scenery, the seating, the roof. Thankfully no one was injured. The theatre was the biggest building in Sheffield. Its outside walls were unusually high and thick and remained intact, preventing the fire from spreading to adjacent buildings or even beyond the block.

The cause of the fire did not require any great forensic examination. Following a very successful pantomime season which ended on 25 February, a production of The Streets of London by Irish playwright Dion Boucicault (1820-1890) began on 11 March. The climax of the drama was the Great Conflagration Scene in which Henry Loraine, as the villain of piece, would set fire to scenery depicting the front of a house. When the "house" was fully ablaze, a small fire-engine and four real firemen, hired from the Liverpool and London Fire Brigade, appeared on stage to put the fire out. In today's Health & Safety conscious world it is impossible to imagine how such a scene could be contemplated.

On the night in question, the performance ended just before 11 p.m. and when the hall had emptied Thomas went over the stage with his stage manager, William Brittlebank. They found some crackers in a bucket and filled it with water. The house lights were switched off about midnight. Thomas then went down to the Adelphi Theatre to check that it was secure and returned to the Surrey Theatre to pick up his coat from his room using a side entrance on Workhouse Lane at about 1.30 a.m. He did not inspect the stage again before going home to Upperthorpe.

The Mayor immediately arranged for a relief fund to support the actors who had lost all their costumes, the band who had lost their instruments and all those in the theatre company who were now out of work. Votes of support were passed for Thomas who had been left in tears as he witnessed fifteen years of work go up in smoke. It was estimated that he had spent between twenty-five and thirty thousand pounds in making the Surrey the finest in the country outside of the capital. The building and contents were insured for £13,000 with the Liverpool and London Company, who had divided the risk amongst four other companies. Any takings from the night of the fire and about a hundred pounds in cash in Thomas's office were also lost. It was a personal as well as financial disaster for Thomas Youdan and also a great loss for Sheffield. As one man put it, "Well, awd rayther it 'ud a bin t' Tawn Hoile."

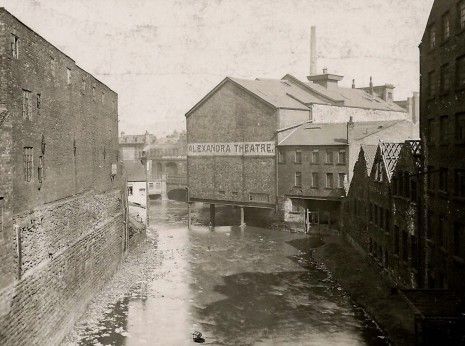

The Adelphi Theatre, which ironically had been used for the construction of the scenery for the "house" fire, now turned out to be Thomas's saviour. Renamed the Alexandra Music Hall, it reopened on 13 October 1865 with a performance by the Sheffield Choral Union supported by other acts. The theatre had been re-modelled and reconstructed, with a larger auditorium capable of holding an audience approaching four thousand.

By February 1866 the Alexandra was being compared to the old Surrey Theatre, further improvements having been made included the installation of a large centre chandelier said to have been designed by Thomas himself. The following month he applied to the Sheffield Excise for a wine licence for the refreshment room which led to an appearance at the magistrates court on 6 April. The application was refused on the grounds that such licences were awarded only to confectioners' shops and the refreshment room did not qualify.

Totley Vale Cottage (Grove House), Hillfoot Road, Totley

Totley Vale Cottage

It was announced that on 23 August 1866 there was to be a sale of furniture and furnishings at Parkwood View, Thomas having decided to move "to the country", probably for his health. He had taken a lease on property then known as Totley Vale Cottage, (Grove House), which was owned by John Gray Waterfall.

Amongst the land that came with the house was a field of wheat about 3¼ acres in extent. Thomas decided upon a novel idea to distribute the ripening crop to the poor, seeking the approval and help of his landlord and Rev. J.T.F. Aldred, the incumbent of Dore. Some 25 of the poorest inhabitants from Dore and 22 from Totley were selected and on Saturday, 14 September the crop was brought in and carted back to the homes of the poor, presumably to be threshed by hand. As a further reward, Thomas offered to buy back any remaining straw that was not of use. When the work was done, three or four hundred people from the two villages were invited to Totley Vale for a supper of bread, cheese and beer followed by an evening of music and dancing.

Thomas was persuaded to stand again for election in the Municipal Elections on 1 November 1866. His nomination came only two days before and whilst the Sheffield Daily Telegraph thought that his return could be counted upon as a fait accompli, his late entry into the election undoubtedly weighed against him and he came third of four contestants, with only the top two being elected to council. Although he was defeated in the election, that did not stop Thomas from taking an active role in the town's affairs. Poor relief was a cause he always championed and in January 1867, when a Soup, Coal and Blanket Fund was being mooted, he immediately offered the sum of £100.

The Youdan Cup won by Hallam F.C. 1867

The Youdan Cup

Thomas Youdan is now best remembered for the silver cup that bears his name. It is generally recognised as the trophy awarded to the oldest football knockout competition in the world, pre-dating the English F.A. Cup by four years. Thomas was not himself a sporting man - he had turned out in charity cricket matches - but he frequently donated prizes for sporting events, particularly for athletics.

There are those who say the idea of a football competition was his alone but equally it may have been suggested to him as a means of promoting his music hall. On 28 January 1867 representatives of thirteen clubs from the Sheffield area met at the Adelphi Hotel, Arundel Street, to draw up the regulations that would govern the competition and codify the rules under which the matches would be played. Three days later advertisements appeared in the Sheffield press announcing a prize competition for the most original and appropriate design for the trophy. The advertisements were placed by Frederick Corbett, honorary secretary for the competition committee and also secretary of Norfolk Football Club. The competition was judged by a committee made up from members of each club. Initially it was announced the winner was a Mr. Jarvis of Roscoe Works, Infirmary Road but soon after it was decided that the honours and money would be divided. A portion of the design by Wainman Topham, an engraver with Messrs. Barras and Co. of Norfolk Street, would be combined with that of Mr. Jarvis. Wainman Topham (1838-1900) later went on to be a landscape artist and was quite well-known locally for his water-colours and pen and ink sketches of old Sheffield. He emigrated to Canada in the late 1880s and had moved to Buffalo, upper New York State by 1897. He died there in 1900 aged about 62.

Sheffield FC, the most prestigious club in the area, withdrew and the competition was held amongst the remaining twelve teams. On 15 February, William Brittlebank printed handbills promoting the competition which ran from 16 February to 9 March. After two knockout rounds there were three teams left: Hallam, Norfolk and Mackenzie. Norfolk were given a bye into the final and Hallam won the semi-final against Mackenzie. Hallam were the eventual winners at Bramall Lane cricket ground. A second place playoff was also contested which was won by Norfolk. Thomas was absent through sickness when the trophies were presented at the Adelphi Hotel on 11 March. The first prize was not to Mr. Jarvis's design owing to the protracted time required for its manufacture. Instead, it was a richly ornamented claret jug created by Ebenezer Hall's silverware firm of Martin, Hall & Co. Thomas later gave a silver dram-flask to Mackenzie, the third placed team, which had three players injured during the competition.

It was intimated that the Youdan Cup would become an annual affair with the Jarvis-designed cup awarded the following year but this did not happen. Nevertheless, Thomas retained a life-long interest in Sheffield football, often awarding prizes at annual general meetings and sports days, particularly for the three teams in the playoffs and for the Garrick club. He also put on benefit evenings at the Alexandra to raise funds for the Sheffield Football Players Accident Society. At the Society's annual meeting in 1872 it was said that without Thomas's continued support the Society would have been defunct.

On 22 November 1867 Thomas bought for £427 property at Totley Bents together with Lower Hare Croft (near All Saints School). Two months later part of this land was sold to Esther Wragg who was then living on Chapel Lane. On 17 December Thomas offered for auction at Totley Vale Cottage, 127 Fat Sheep (Leicester, Lincolnshire, and cross-breds) which were said to be of first rate quality having been well fed on linseed cake, turnips and corn. On Christmas Day the children of Dore and Totley Schools were presented with 6d. each by Harriet Youdan and her friend Rosetta Roland Beal, the daughter of Alderman Michael Beal, a watchmaker and jeweller. At Dore School on New Year's Eve, Harriet and Rose presented the poor women of Dore and Totley with a half-pound of tea each and on 7 January 1868 the same two ladies presented another half-pound of tea to each of the mothers of children at Totley School who had been the best attenders.

Thomas and Harriet's stay in Totley appears to have come to an end around 22 April 1868 when the whole of their furniture, furnishings, paintings, kitchenware etc. plus horses, carriages, pigs, Alderney cattle and farming equipment were put up for sale at a two-day auction. There was nothing in the newspapers to indicate why they were leaving or where they were moving to. Certainly, Thomas had been keeping a close watch on the progress of a proposed railway line from Sheffield to Chapel-le-Frith. The line as described would have been very similar to that constructed more than twenty years later except that it skirted Totley Vale, crossed the Dore to Totley road and entered a 5,280 yard tunnel above Oldhay mill to emerge at Padley. It would have cut through Thomas's private drive to Abbeydale Road and made the daily journey by carriage to Blonk Street a longer one.

Alexandra Theatre, rear built over River Sheaf at its confluence with River Don.

The Alexandra - "Tommy's Place"

On 29 July 1868 Thomas applied for a wine licence for the Alexandra Music Hall. Alterations had been made to the premises to make a separate entrance from the road and staircases to rooms on two floors where there were counters serving biscuits, pies, confectionary etc. as well as hot cooked meals on demand. Waiters were on hand all day from around 9 o'clock in the morning. The court had to agree that the place was now fitted out to qualify as an eating-house and as there was no opposition the licence was granted. Thomas returned to court on 26 October to apply for a twelve month licence to perform stage plays. He had, of course, held a theatrical licence for the Surrey Theatre at the time it burned down. Again there was no opposition and, when the Mayor granted the licence, there was a burst of applause from the spectators.

The name of the premises was changed to the Alexandra Opera House and Music Hall - although most people called it The Alex or Tommy's Place. Further alterations to the theatre were made in time for the Christmas pantomime, the most important of which were a new set of luxury boxes. It had taken just three and a half years for Thomas to restore his business to the position it was in before the fire. The annual applications for alcohol and theatrical licences would in future be plain sailing.

For Thomas's Christmas gift in 1869, Harriet and Rose were again on hand to help distribute two thousand half-pounds of tea to the aged, poor and needy of Sheffield. The distribution took place at a packed Cutler's Hall to recipients who had been recommended by clergymen of all denominations throughout the town and by officials connected with various organisations including the Foresters, Druids, Oddfellows, Rechabites and other sick clubs enrolled under the Friendly Societies Act. A further gift of 150 half-pounds of tea was made to the striking miners at Mr. Huntsman's Tinsley Park Colliery.

Semi-retirement

On 25 March 1870 Thomas and Harriet moved into a large farmhouse at Flotmanby, a few miles inland from Filey. Some wealthy men took up farming later in life as a means of making losses to reduce inheritance taxes but Thomas seems to have genuinely enjoyed being a farmer. It was in the blood; he was an agricultural labourer in early life. He bred livestock, judged amateur agricultural competitions and was a vice president of the Scarborough, Hackness and North and East Yorkshire Agricultural Society.

Whilst out riding on 30 August 1870, Thomas was thrown from his horse, landing on his head. Although well enough to remount and ride home, Thomas was concussed and was still recovering from the accident a week later. He was now in semi-retirement, having left the day-to-day running of the Alexandra to his manager and friend William Brittlebank (1829-1897). The two had been in business together at least sixteen years. William was a printer by trade like his father. He was apprenticed at the Sheffield Iris and later went to work at the Caxton Printing Office at 7 Mulberry Street where another workman was Tom Greaves. When the proprietor, Mr. Wrigley, died in 1855 Thomas purchased the business, retaining William and Tom as his chief assistants. An arrangement was reached whereby they would acquire ownership of the business from Thomas in exchange for printing all his playbills and acting as the manager and secretary for the Surrey Music Hall.

In February 1871 Thomas permitted his name to appear on nominations to fill a council vacancy in St. Philip's Ward when it seemed there would be no other candidate. However, as soon as Joseph Gamble, a steel and file manufacturer, was nominated Thomas withdrew and Mr. Gamble was elected unopposed. The nomination papers gave Thomas's address as the Victoria Hotel on Furnival Street. Evidently Thomas was in the habit of visiting Sheffield about twice a week and he stayed there regularly. He was in the hotel on census night, 7 April. Harriet Youdan was a visitor at 30 Havelock Street, the family home of her friend Rose, who had married Walter Stanton, an architect, the previous month at St. George's, Brook Hill. Harriet, now styling herself Harriette, was one of the two witnesses to sign the register.

On 26 October 1871 Thomas again allowed his name to put forward for the forthcoming Municipal Elections. This time it was for a vacancy in the Attercliffe Ward where the only other candidate was Ralph Skelton, a spade a shovel manufacturer, who was standing for re-election. Once again, Thomas was late entering the fray. Mr. Skelton, a teetotaller, had the support of two associations of burgesses, the leading members of the temperance movement and the religious community. He was seen everywhere addressing meetings whilst Thomas refused to campaign at all.

He did, however, have the support of the beersellers and the miners "to a man". As well as the donation of tea, already mentioned, he had earlier given the strikers 600 6d. four-pound loaves and donated at least £65 to their Widows and Orphans Fund. On election day, 1 November, Ralph Skelton was the victor by 855 votes to 609. With just two days of campaigning by his supporters and without making a single appearance in the constituency, it was perhaps remarkable that Thomas garnered so many votes.

Later Life

In April 1874 Thomas retired from business and, after many years as its manager, William Brittlebank became the lessee of the Alexandra. The annual application for a theatrical licence was not until 10 December when there was full support for the renewal of the licence.

Thomas still owned the site on West Bar of the former Surrey Theatre. After the fire the site had been made safe and some of the walls had been pulled down. There was a large sale of firewood, boilers, ovens and other metalwork and then the site was properly fenced off. Various schemes had been proposed for its use but none had come to fruition. In July 1874, however, it became known that Thomas was proposing to build a public salt-water aquarium on the ground floor and to erect a concert hall above it. The aquarium would be similar in concept to the one in Brighton, designed by the celebrated pier architect, Eugenius Birch, and opened in 1872. Sea water would be brought daily from Grimsby and raised by steam power to a reservoir on the roof from which it would flow into several tanks. Also like Brighton, the aquarium would have other attractions including a fernery. The concert hall would be nearly as large as the main auditorium in the Albert Hall. It would not have daily performances but would be used only when hired.

By 9 April 1875 Thomas's ambitious scheme had been abandoned because of the logistics of transporting the sea water so far inland and he had no further use for the land. He gave instructions to place advertisements for its sale. An auction was advertised for June but it did not take place until 28 September 1875 at William Harvey's saleroom on Bank Street. Well before the allocated time, the room was filled with interested parties including victuallers and music hall proprietors. On offer was a plot of about 1,292 square yards together with all the (burned out) buildings and materials thereon. An opening bid of £5,000 was raised three times in £500 increments before Mr. Harvey consulted with Thomas who indicated that if the bid were to be raised by a further £100 it would be accepted. That information was conveyed to the saleroom but as no such offer was forthcoming, the lot was withdrawn.

On 4 February 1876 it was reported that the old Surrey Theatre site would be purchased by George Wostenholm, of Washington Works, for the purpose of building a mission but that too did not come to fruition. A few weeks later another proposal was for the formation of a company with a capital of £10,000 made up of 2,000 shares of £5 each. The theatre site would be purchased from Thomas for £8,000, comprised of £6,000 in cash and £2,000 of shares. The proposal was to build a billiard hall on the ground floor and above it a skating rink that could be covered at times for use as a ballroom. Once again, nothing came of the scheme.

By the spring of 1876, Thomas's health was deteriorating. He suffered from bronchitis and gout. His physician, Dr. Charles William Dawson, in practice at Hunmanby, insisted that he go for the air to Southport and on his return Dr. Dawson thought he looked much the better for it. Thomas visited Sheffield on 8 September, lunching with William Brittlebank and then visiting his solicitors, Messrs. Broomhead, Wightman and Moore of George Street. He returned to Flotmanby the next day, spending some time in Scarborough. On 12 November, Dr. Dawson received a letter from Harriet asking him to visit Thomas urgently and found him to be suffering from apoplexy (cerebral haemorrhage) from which he never fully recovered. A second stoke on the 26th proved fatal. He died at Flotmanby House two days later, aged 60. By his own reckoning, the Surrey Theatre fire had taken ten years off his life. On 1 December Thomas's body was conveyed to Sheffield by train where it was met by William Brittlebank and that afternoon he was buried in the General Cemetery.

Thomas Youdan memorial stone, General Cemetery, Sheffield

After the Funeral

The purpose of Thomas's visit to his solicitors on 8 September 1876 was to make a new will leaving his entire estate to his niece Harriet. She was unmarried at that time but on 5 April 1877 she was married to Frederick Stanton, an architect and surveyor, at St. John the Evangelist, Folkton, near Filey by Rev. Robert Mitford Taylor. Frederick was a younger brother of Walter Stanton, the husband of Harriet's friend Rose Beal.

The will, however, was not accepted by a number of Thomas's relatives. Siblings Samuel, John, Sarah, Anne, Jane and possibly Hannah were still living. The case of Stanton and Wife v Youdan came to Leeds Assizes on 31 August 1877 when Thomas's oldest surviving brother, Samuel, disputed the will on the grounds that it had been made when Thomas was of an unsound mind. The court was told that Thomas had no children of his own but his niece Harriet had lived with him since 1849 when she was three years old. He loved her as his adopted daughter and she loved him as her adopted father. He had spent money on her lavishly and sent her to Paris to be educated. Harriet had met her future husband in 1870 and become engaged to be married. For a while she lived away from home but in 1871 the engagement was broken off and she returned to live with Thomas.

Witnesses were called including William Brittlebank, Dr. Dawson, Rev. Taylor and Dr. T. Goodman of Southport to testify that Thomas was of sound mind. His solicitor, Edward Moore, gave evidence about the will which he had drawn up himself on the day in question. He had cautioned Thomas about leaving everything to Harriet but Thomas had been most insistent that she was to be the sole benficiary and that there were to be no other family legacies. On hearing the evidence presented, Samuel Youdan abandoned his case and the court found in favour of the Stantons.

Thomas's land at Totley Bents came up for auction by William Harvey the following month. Bents Croft, containing 1a. 2r. 3p., lay between Strawberry Lee Lane and Moss Lane and was bounded on the east by Bents Lane (now Lane Head Road). It realised £270. Great Green, containing 2a. 1r. 21p., adjoined on the east (and presumably is now the top end of the cricket field). It was knocked down for £220. In September 1878 the old Surrey Theatre site was acquired by the Guardians of the Sheffield Union and Overseers of the Township of Sheffield for the sum of £6,500. Harriet was now a very rich woman having inherited around £25,000 (£3m in today's terms) but that was not the end of the her troubles with the family.

John Youdan, Thomas's brother, was brought up at the Second Court at Sheffield Town Hall on 25 September 1879 to answer a summons by the Sheffield General Cemetery Company that he willfully defaced the inscription on Thomas's memorial stone, contrary to the Sheffield General Cemetery Act of 1846. Walter Stanton gave evidence that he had personally supervised the erection of the memorial which was of a very hard stone, Aberdeen granite, and which cost £200. On the monument was the following inscription:

THIS MONUMENT

IS ERECTED

TO THE BELOVED MEMORY

OF THE LATE

THOMAS YOUDAN

OF THIS TOWN

BY HIS ADOPTED DAUGHTER

HARRIETTE YOUDAN.

HE DEPARTED THIS LIFE

NOVR. 28TH 1876

AGED 60 YEARS.

REQUIESCAT IN PACE.

William Lomas, a stone engraver, testified that he saw the defendant on 25 August 1879 chipping the monument with a hammer and chisel and asked him what he was doing. John replied that he had cut out the words "adopted daughter" adding that "someone had put it in that had no right to do so, as it was not true." Whilst admitting the offence, John continued to dispute that Harriet was Thomas's adopted daughter stating that, "He never did adopt her" and that she was his niece. He wanted "the truth to be known to succeeding generations." Quite what John Youdan meant by that we will never know. Was he disputing the inheritance or was there some sort of family scandal? The Bench fined him the full penalty of £10 plus costs, or two months' imprisonment. John either couldn't or wouldn't pay the fine and so he spent the next two months in Wakefield Prison and was discharged on 24 November 1879.

Plaque, Sheffield United F.C., Cherry Street, Sheffield

Epilogue

There are few traces of Thomas Youdan left for us to see today. His Surrey Theatre was burned to the ground in 1865. The Crimean War memorial which he championed has been taken down and is in store, very badly damaged. The Alexandra Opera House was demolished in 1914. Only one rather blurred picture of Thomas survives, thanks to Councillor Frederick Bland (1860-1934) who photographed it from an original print in the Mitre Hotel, Change Alley in the 1920s. The Youdan Cup, lost for many years, was rediscovered in 1997 and now rightfully belongs to Hallam Football Club who bought it for £1,600 from a Scottish antiques collector. Sheffield United remember Thomas in one of a series of plaques on the perimeter fence at Bramall Lane where the final of the cup competition was played. His name is spelled Youden which, whether by accident or design, is the same spelling that was used to record his baptism and those of his nine siblings in the parish register at St. Oswald Parish Church, Kirk Sandal.

Some of the people we have researched are heroes and others are scoundrels. Thomas Youdan was both. He abused the licensing laws when it suited him; he was lucky not to be imprisoned for holding an illegal lottery; and he was found to have lied in court when he took advantage of a fifteen year old employee. He was also an energetic and imaginative man who made, lost and gave away fortunes and in so doing brought enjoyment to thousands of ordinary people in Sheffield which had a much richer music hall history than other provincial towns. He gave them a free museum and art gallery when there were none, and opera and drama at affordable prices. He supported the poor, sick, elderly, unemployed, and orphaned with real, practical assistance - money, tea, bread, cake, beef, soup, blankets, coal, even swedes and wheat. In his biography of Thomas Youdan for Totley Independent Issue 21 and its summary in Drawings of Historic Totley, Brian Edwards made no mention of the Youdan Cup nor of Thomas's philanthropy. Instead he remembered Thomas Youdan for his undercooked, monster cake. We think he deserves rather better.

June 2021