A Totley Entrepreneur: John Dyson, 1789/90-1858

John Dyson was born in the Parish of Norton and baptized at St. James’ Church. The parish encompassed Totley at this time, as well as all of Heeley, so it is difficult to pinpoint exactly where his parents lived. He became a scythe grinder, probably having served his apprenticeship at one of the many wheels on the River Sheaf that bordered the parish.

He first rented the Abbey Dale Works site during 1820s, forming various working partnerships with Biggin, Carr and Vickers, names that would become synonymous with the steel manufacturing industry. There is evidence supporting the improvement of the crucible steel making workshop at Abbey Dale during this period. Then in 1830 he declared an end to his latest partnership of Dyson, Biggin & Co. and created his own company, John Dyson & Co. Once in charge of his own destiny he began improving and expanding the forge and gained more control of his supplies and ‘production line’. He built and moved into the Manager’s house on site. He also built stabling, storage and a new counting house, and re-jigged the use of existing buildings.

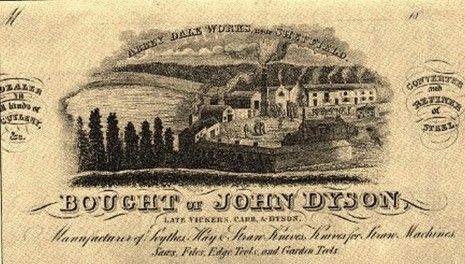

By 1832 this impressive letterhead was being used on his invoices and shows the forge almost as it appears today.

He established Dyson’s Brickworks on Totley Moor in 1832/3, where he also mined the ganister from which his crucibles were made. A constant supply was needed as the pots only lasted for a few firings. Then in 1836 he bought and modernised Totley Rolling Mill, which allowed him to expand further by transferring that part of the process from the Abbey Dale Works. This created a space that became the finishing area for his edge tools, and storage for goods awaiting shipment.

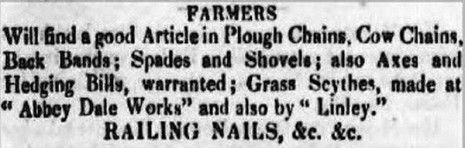

He was a man with ideas and ambition. During the decade his products appear to have gained custom and kudos. They were prized for their quality and could be purchased across the country, as seen in this chandler’s advertisement from the Carlisle Journal in 1838.

However, all was not running smoothly as the formation of Unions was giving the workers courage to defy their bosses, to question working conditions and their rates of pay. As early as 1832 Dyson, in a letter to a Skipton customer, apologises for only supplying part of the order, due to trouble from the Grinders’ Union, ‘you cannot get them to work as they should do’.

In 1840/41 Dyson had a lengthy disagreement with a worker who had refused to grind some hay knives. The man knew that other employers were paying a higher rate per dozen and as a consequence had walked out on more than one occasion, despite being ordered back, firstly by Dyson and then the Courts. The case was fully reported in the Sheffield press and would have brought Abbey Dale Works to the notice of agitators in the Grinders’ Union who looked for employers they considered to be unfair.

The following year the Works was targeted and an explosion destroyed the Grinding Shop. It was the early days of the ‘Stirrings in Sheffield’ when vandalism and destruction were wrought on many works by agitators in the Unions. Sometimes it was just ‘rattening’ of the leather straps that drove the machinery (Abbey Dale had had these attacks too), but other destruction could be greater, as in this explosion, and even murders took place.

Dyson was uninsured, and with production at a standstill was declared bankrupt within a few short months. This was announced in the press throughout the country, specifically in Perry’s Bankrupt and Insolvent’s Gazette, where he would be listed each month until discharged. The discharge would then be announced in the same manner. Many bankrupts were jailed, but there is no evidence that this fate befell Dyson.

In 1844 an auction took place over a period of three days, at the sites of his once thriving business.

Dyson’s tenancy at Abbey Dale came to an end in 1848, leaving behind a debt of £407 (almost £39,000 at present day values). Maybe the Courts had thought that by using the undamaged parts of the forge he had a chance to clear his debt, but clearly this had not happened.

In the census of 1851 he is to be found living at 67, Fitzwilliam Street, running a beer house. He died in Bradway in 1858 and was buried at Norton Parish Church, where he had been christened almost seventy years previously. Every indication is that he never cleared his debt. The Courts had continued to monitor his ‘worth’ annually, but at his death it was declared to be ‘under £100’, the lowest level on their scale and accounting for just the goods and chattels of his home. A sad end for the man whose entrepreneurial skills might have brought him great wealth in less volatile times. Although three men were arrested following the explosion, no one was ever convicted of the crime.

‘Rattening’ was a term given to the damage inflicted on the expensive leather belts that drove the machinery, said to resemble gnawed teethmarks made by rats.

The recent name of the Refractory on the original site of Totley Moor Side is coincidental. I tried to find a family link between John Dyson in this story and the Stannington firm (Dyson Refractories Ltd) who bought it some 50 years ago, but failed. However I like to think that maybe our John got his inspiration (and expertise) from a common ancestor!

Pauline Burnett