‘Derbyshire is a lovely child’s alphabet’: Ruskin, Railways, St. George's Farm and Totley's Heritage

by Andrew Russell

There seem to be two important dates in Totley's history which are relevant to this article. The first is May 1842, when the Totley Enclosure Act was passed, giving away Totley's common land to a few wealthy and distinguished landowners. The landowners' rights became 'almost absolute' and 'people's rights [were] effectively, nonexistent' [1]

The second date is 1935, when Totley, Dore and Greenhill were taken in by the City of Sheffield, away from the county of Derbyshire. The long development of the railways took place between these two dates, specifically the outward growth of the railway from Sheffield to Totley in the early to mid-1870s, and then into Derbyshire and beyond to Manchester in the 1880s and 1890s. This was a period when many rural communities were joined to towns and cities. Sheffield expanded to Totley. Links between towns, cities, villages and counties all over the country would change forever.

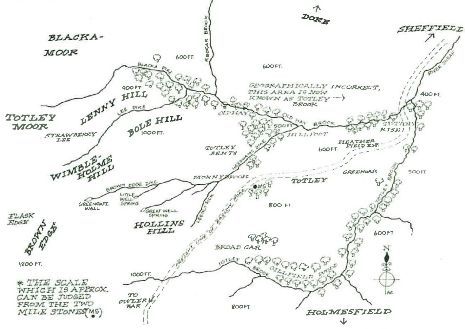

The Saxon origin of the name Totley indicates the settlement of 'Tot' or 'Toft' on the hill amidst the open clearings. As a 'look -out' it provides glorious views extending for miles. [2] Totley includes land situated from about 400 feet below Totley Rise, climbing to 1300 feet at Flask Edge on its far south-western border. It grew to cover an area of some three and a half miles by two miles, by the nineteenth century. It is an area of fast-flowing streams, abundant in wood—and with the local gritstone, Totley had all the raw materials necessary for the grinding-wheels in the watermills were dotted along the local streams and tributaries that ran into the River Sheaf at Totley Brook, and on to Sheaf-field, or Sheffield, some six miles away. From medieval times, lead smelting and rolling, paper-making, corn-grinding and scythe-making were prominent at various stages, although much of the workforce remained engaged in agriculture.

Totley: the main natural features (by Brian Edwards)

Over the centuries, Totley had consisted largely of a succession of farms and farming communities. In the medieval period, Totley's land was close to Beauchief Abbey in the parish of Ecclesall—an abbey in a dale. The Abbey was founded by Robert FitzRanulf in 1183 and had mills on the River Sheaf. The monks residing there farmed sheep, for fleece and mutton. By the 12th century they had a sheep grange at Streberry-ley (Strawberry Lee) in Totley Bents. Whilst the Abbey is still partially standing, and the old ponds which supplied the monks with their carp remain, [3] the original pasture of their sheep grange can only be traced through old documents.

Beauchief Abbey (by Brian Edwards)

Brian Edwards traced out a route through Totley by which the monks would have taken their flocks of sheep over the course of the year, a journey made for almost three hundred years until the Dissolution of the Monasteries. This rich medieval history would have been looked on approvingly by Ruskin, and he might have felt that 'in the main temper of its inhabitants, old English, and capable, therefore, yet of ideas of honesty and piety by which Old England lived.' [4]

Ruskin outlined a bucolic vision in the first number of Fors in 1871 that suited rural Totley well:

We will try to take some small piece of English ground, beautiful, peaceful and fruitful. We will have no steam trains upon it and no railroads; we will have no untended or unthoughtful creatures upon it; none wretched, but the sick; none idle, but the dead .. , [5]

This is the spirit in which Ruskin approached the creation of St. George's Farm in Totley where:

A few of the Sheffield working men who admit the possibility of the St. George's notions being just, have asked the to let them rent some ground from the Company, whereupon to spend the spare hours they have, of morning or evening, in some useful labour. [6]

The communal farm at Totley was started by a group of men shortlisted by Henry Swan, the Curator of the Guild of St. George Museum in Walkley, Sheffield. Edward Carpenter, socialist, poet, philosopher, and early gay activist, was influenced by and wrote to Ruskin, describing them:

A small body—about a dozen—of men calling themselves Communists, mostly great talkers, had joined together with the idea of establishing themselves on land somewhere; and it was at their insistence that John Ruskin bought a small farm (of thirteen acres or so) at Totley near Sheffield, which he afterwards made over to St. George's Guild.

Carpenter followed the fortunes of St. George's Farm and lived close by in Bradway, and on inheriting money from his father, he established himself at Millthorpe, near Barlow, Derbyshire for a simpler life closer to nature, a life of market gardening and rural craft. The period from 1877 onwards marks a chequered history for St. George's Farm, as so well outlined in Frost's new book, The Lost Companions. [7] When John Ruskin visited his new venture some two years later, on 17th October 1879, all seemed—at least on the surface—to be going well. Ruskin cheerfully described his 'faithful old Gardener' David Downs, as resident 'for a while at least, at Abbeydale' [8] to look after the communal agricultural project with Riley 'in feathers' and 'especially proud of some rows of cabbages'. Ruskin tells us that he 'had tea in state at Totley and looked at all the crops.' [9] Yet, as Frost points out, 'relations remained cordially guarded.' [10] In fact, after his visit, Ruskin decided to remove Riley from St. George's Farm and leave the management to Downs. This marked a phase where the Totley 'experiment' went through a difficult period.

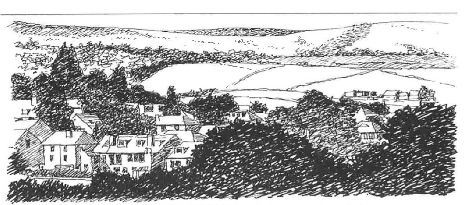

View over Totley from near Mickley Lane (by Brian Edwards)

Yet, on that day's visit, Ruskin must have seen around him the beautiful Derbyshire countryside, which is reflected in a line in a letter he wrote to the Manchester City News in 1884: 'Derbyshire is a lovely child’s alphabet; an alluring first lesson in all that’s admirable and powerful, chiefly in the way it engages and fixes the attention,' [11].

William Harrison Riley had come to Sheffield in 1877. He edited The Socialist from June to December of that year, sending a copy to Ruskin, who, with some guarded comment and criticism, thought there was a great deal of good in it. Riley took centre-stage in the St. George’s Farm community for a period in 1878. Like Carpenter, he was an admirer of the American poet Walt Whitman, and looked for a communal agrarian life. It was a project nourished 'by a vague but persisting recollection of a past Golden Age ... a Garden of Eden separated in time and space from the realities of common life.' [12] Totley fitted this description, in that it had been long protected by the green band of Whirlow, Ecclesall Woods, Ladyspring Wood and Beauchief Hall—hidden and remote from Sheffield’s industrial sprawl.

Yet in the late 19th century, change was accelerating everywhere and one of the main agents in this, as I started out by saying, was the growth of the railways. Prior to the Sheffield railway line reaching Dore and its immediate neighbour, Totley, there was just one horse-drawn bus per day which travelled out from Sheffield covering the six or so miles to this area. This must have entailed a long and often difficult journey; especially in the autumn and winter. With the opening of the railway station in 1872, there were trains carrying far more people out to Dore and Totley and with greater frequency, at speed and with protection from the weather. Land prices rose as a result, and even before the arrival of the railway, plans for suburban villas were being drawn. Sheffield men were coming to the rural village of Totley. Symbolically, with the building of Dore and Totley station, the site of the medieval Walk Mill—which the monks of Beauchief Abbey had worked, frilling (cleansing) their cloth—was demolished, and the dam that powered the mill was filled in. A few years later, Ruskin, apparently looking back to the monks at Beauchief Abbey, described his St. George Farm workers as 'in the spirit of monks gathered for missionary service.' [13] He always preferred to call the Totley farm 'Abbeydale' providing a link back to the Abbey at Beauchief.

Already in the summer of 1873, the Totley Brook Estate Company, made up of a brush manufacturer, a County Court Clerk, a timber merchant and two building contractors—Sheffielders all—was planning new housing. As Brian Edwards rightly points out, 'The railway was the turning point in the development of the [Totley] district.' [14] The railway ushered in an era of building that gained momentum in the decades that followed.

St. George's Farm, Totley

St. George’s Farm, led first by Edwin Priest and later by Riley, hosted fellow travellers during 1878, who were dropping in to lend a hand, discuss politics and poetry and crack intellectual jokes.

Many visitors went to the farm, and newspaper correspondents had things to say about us, wise and otherwise. Now our expenses were increased and we had to meet them, so we had parties to visit during the summer taking tea, for which they were charged. ... Every Wednesday, we went to Dore and Totley [station] from Sheffield, bringing back fruit, eggs, and vegetables to the meetings which the members purchased. [15]

The Totley Brook villa estate started in 1873, later failed as the land and its planned housing was bisected by the incoming railway as it reached Totley. Another very grand enterprise, though short-lived, took shape in the mid-1880s, initially rooted entirely in land speculation. Alderman Joseph Mountain, one of Sheffield's building magnates, planned a pleasure garden that would rival the Belle Vue Gardens in Manchester. Many used the railway to go to the opening of Victoria Gardens which lay on a piece of land bordered by Baslow Road, Mickley Lane and Totley Brook. Opened on Whit Monday, 1883, the ceremony attracted 10,000 people who enjoyed a variety of theatrical entertainments; there was a ballroom, and refreshments were served (the restaurant roof and walls were mostly made of glass) and there was a 400-yard promenade with extensive views over the Derbyshire Moors. The grounds were later laid out for cricket, tennis, bowls and archery, and later still for cycle racing. [16] Local landowners were not happy with this large development. A drinks licence was refused, and in 1886, Mountain was summoned on grounds of a breach of the Public Health Act, for permitting raw sewage from one of his Totley Rise properties to drain into a local landowner's lake. By 1887, the venture was failing. When Joseph Mountain died in 1893, the Victoria Gardens were offered for sale.

Victoria Gardens (by Brian Edwards)

Meanwhile, David Downs, Ruskin's gardener, continued looking after St. George's Farm, which was operating at a financial loss, and when he died in 1888, the land was let to John Furniss, George Pearson and others. Furniss was a considerable figure among the Sheffield Socialists, an old-style preacher and an impressive speaker who used Totley as a base for his political activity. [17]

In the autumn of the following year, St. George's Farm was visited by G. L. Dickinson and C. R. Ashbee, two young Cambridge idealists staying at Millthorpe with Edward Carpenter. Ashbee recorded his impressions of the new commune:

There we have a community of early Christians pure and simple— some ten men and three women ... and no private property except in wives ... there was a brightness and clearness in the faces of most of them which bespoke enthusiasm for humanity. [18]

The Pearson family, who made a commercial success of running the farm at Totley.

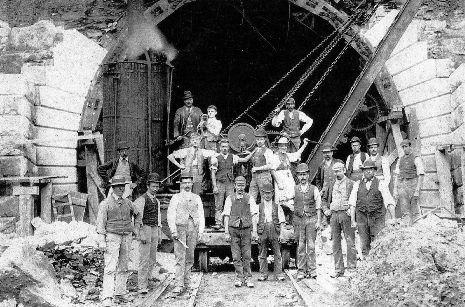

By the end of the 1880s, the Guild of St. George offered George Pearson the farm rent-free for a couple of years, until he could afford to pay. Ironically, it was largely the building of the Totley railway tunnel to Grindleford, linking it up with the line to Manchester, that put Pearson in profit. He found a regular market among the railway navvies, and despite the smallpox outbreak in Totley at the start of the 1890s, he continued to do well, even when other tradesmen were less fortunate. So it was largely the railway that revived the fortunes of the Guild's farm, and put Pearson on the path to success. By 1935, he had seven greenhouses and a packing shed, he grew bedding plants, tomatoes and cucumbers, and had by then bought neighbouring land; the owner of 43 acres. By the time Totley became part of Sheffield and the utopian dream had faded, and before the farm had become a flourishing commercial concern, the Guild had sold the farm to him outright.

Yet for a while, at least, Ruskin's scheme had given some land back to a community of people, and had looked back to an age of Common Land which had been undermined by the Enclosure Acts. It had given a small group of Sheffield men, who had dreamed of a communal enterprise away from the town, the opportunity to experiment. These people had political ideas that were new, though, in part, rooted in the Chartist movement. The Totley Farm shows how fraught with difficulties such a communal project was. Ruskin—in choosing the rural and remote Derbyshire village of Totley, at a time when the railway he abhorred was rapidly opening the area up to speculation, change and enterprise— became an important part of the local history before Totley left Derbyshire and became a suburb of an industrial city in South Yorkshire.

This article is in part a tribute to Brian Edwards, who died in February of this year on his 78th birthday. Illustrations from his publications, Brian Edwards' Drawings of Historic Totley (1979), Totley and the Tunnel (1988) and Dore, Totley and Beyond (1993) have been reproduced with the kind permission of his widow, Pamela Edwards.

The building of the Totley Tunnel.

Notes

1. Only connect: soil, soul, society: the best of Resurgence Magazine 1990-1999 (2000), p. 61 ed. John Lane and Maya Kumar Mitchell (Totnes: Green Books).

2. Brelsford, Vernon (1954) A History of Dore and Totley from the ninth to the twentieth centuries, p.3 (Chesterfield: Wilfred Edmunds).

3. Edwards, Brian (1996) Dore, Totley and Beyond: the -drawings of Brian Edwards, pp. 8-9 (Great Longstone: Brian Edwards).

4. Works 30.52, and qtd. In Walton, Mary (1949) Sheffield, its story and its achievements, p. 225. 2nd ed. (Sheffield: Sheffield Telegraph & Star Ltd).

5. Works 27.96.

6. Works 29.98.

7. Frost, Mark (2014) The Lost Companions and John Ruskin’s Guild of St. George: a revisionary history (London & New York: Anthem Press).

8. Rosenbach Museum Library 6.135.

9. Ruskin Library MS L42 2003L04889

10. Frost p. 170.

11. Works 34.571. Qtd. In Edwards, Brian (1985) Totley and the Tunnel, p.14 (Sheffield: Shape Design Shop).

12. Hardy, Dennis (1979) Alternative Communities in Nineteenth Century England, p.2 (London & New York: Longmans).

13. Price, David (2008) Sheffield Troublemakers: Rebels and Radicals in Sheffield History, p.72 (Chichester: Phillimore & Co, Ltd),

14. Edwards, Totley and the Tunnel, p.4.

15. Maloy, M., 'St George’s Farm' in Commonweal (25th May 1889), p. 165

16. http://www.totleyhistorygroup.org.uk/people-of-interest/joseph-mountain/

17. Marsh, Jan (2010) Back to the Land: the Pastoral Impulse in Victorian England 1880-1914, p. 97 (London: Faber & Faber).

18. C. R. Ashbee, entry for 4.9.1886, Memoirs (1938) vol. 1, p.31. Unpublished. Qtd. in Marsh, p. 98

The Yard at St. Georges Farm

Nellie the engine (by Brian Edwards). The coming of the railway transformed the Derbyshire village of Totley into

the modern suburb of a commercial city in South Yorkshire.